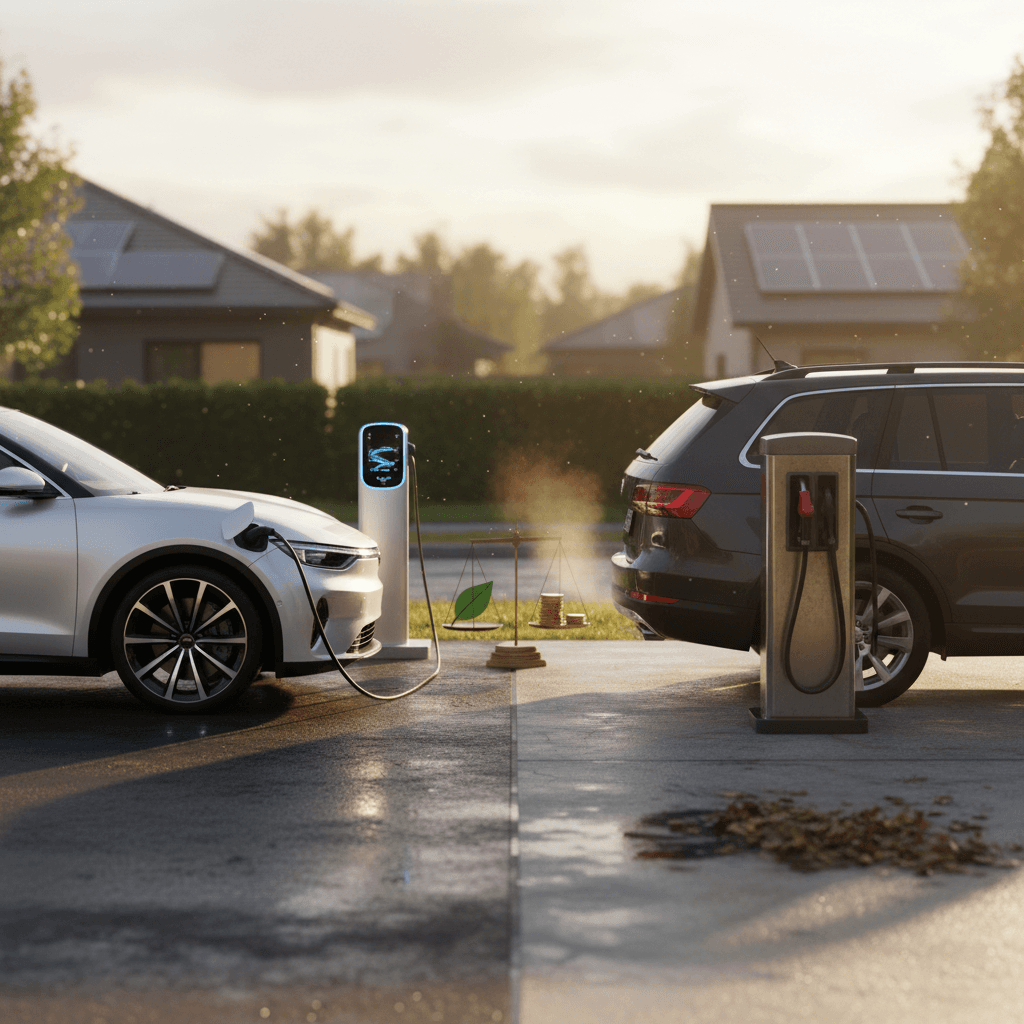

When people talk about “electric and gas vehicles,” it usually hides a tougher question: which one actually makes more sense for you over the next 5–10 years? Between EV headlines, hybrid hype, and political whiplash on incentives, it’s easy to feel stuck. This guide cuts through the noise, using 2024–2025 data and real‑world trade‑offs so you can decide if your next car should plug in, fill up, or do a bit of both.

Quick snapshot

Electric and gas vehicles in 2025: what’s actually changing

Electric and gas vehicle market snapshot (U.S.)

The takeaway: the era of only‑gasoline vehicles is over, but we still live in a mixed fleet. For the next decade at least, most households in the U.S. will own a combination of electric and gas vehicles, or one vehicle that blends both, like a hybrid or plug‑in hybrid. The right answer for you depends less on the headlines and more on your driving pattern, housing, and budget.

Think in use‑cases, not labels

How electric and gas vehicles work under the skin

Gasoline vehicles (ICE)

- Engine: Burns gasoline in a multi‑cylinder engine to create power and heat.

- Drivetrain: Power passes through a multi‑speed transmission, driveshafts, differential.

- Energy storage: Fuel tank; energy density is high, so range is easy to achieve.

- Key traits: Fast refueling, dense fueling network, more moving parts and fluids.

Battery‑electric vehicles (BEVs)

- Motor: One or more electric motors provide instant torque with far fewer moving parts.

- Energy storage: High‑voltage lithium‑ion battery pack under the floor.

- Charging: Plug in at home or public chargers; no tailpipe or fuel tank.

- Key traits: Quiet, quick, low routine maintenance, but charging takes planning.

Between pure electric and pure gas sit hybrids and plug‑in hybrids (PHEVs). They pair a gasoline engine with an electric motor and battery pack. Hybrids can’t generally plug in; they just use electricity captured from braking to boost efficiency. PHEVs add a charge port and a larger battery, giving you 20–60 miles of electric driving before the gas engine takes over.

Terminology trap

Upfront price, incentives, and financing

New EVs still tend to cost more than comparable gas cars on the sticker, but the gap has narrowed. Incentives, dealer discounts, and used‑EV pricing often flip the script, especially if you’re flexible on brand and open to buying pre‑owned instead of new.

Typical price ranges by powertrain (new mainstream models)

Big luxury and specialty vehicles can fall outside these bands, but these ranges describe many 2024–2025 mass‑market models before incentives or discounts.

| Powertrain | Typical MSRP band | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gasoline (compact–midsize) | $25,000–$40,000 | Broadest selection; heavy discounting in some segments. |

| Hybrid (non plug‑in) | $28,000–$45,000 | Usually a small premium over the gas version of the same car. |

| Plug‑in hybrid | $35,000–$55,000 | Limited selection; some qualify for incentives depending on sourcing rules. |

| Battery‑electric | $32,000–$60,000+ | Compact crossovers now starting in the low $30Ks; pickups and premium brands much higher. |

Approximate U.S. MSRP ranges, excluding taxes and destination charges.

Incentives are in flux

How financing affects electric vs gas costs

The same monthly payment can hide very different 5‑year economics.

Upfront vs monthly

Many buyers focus only on the monthly payment. An EV with a higher price but lower fuel and maintenance costs can still be cheaper over 5 years, even if the payment is slightly higher.

Interest rates & terms

Longer terms reduce the monthly cost but increase total interest. That matters more for higher‑priced EVs. Run the numbers, not just the payment.

Used EV opportunity

EVs have seen steeper depreciation than gas cars in recent years. That’s bad for first owners but good for you if you’re buying a used electric vehicle with plenty of battery life left.

Where Recharged fits in

Fuel vs electricity: what you really pay per mile

Gasoline prices move with global oil markets and politics; electricity prices vary by state and utility. But across most of the U.S., home charging still beats gasoline on a cost‑per‑mile basis, while public DC fast charging can approach or even exceed gas prices per mile.

Gas vehicles: fuel costs

- Typical efficiency: 25–30 mpg for many crossovers and sedans.

- At $3.50/gal: That’s roughly $0.12–$0.14 per mile.

- Volatile: Prices can spike over $4 or drop below $3 depending on the year and region.

EVs: electricity costs

- Home charging: Many EVs use 0.25–0.35 kWh per mile. At $0.15/kWh, that’s ~$0.04–$0.05 per mile.

- Public DC fast charging: Often $0.30–$0.50/kWh, or around $0.09–$0.17 per mile.

- Time‑of‑use rates: Some utilities offer cheaper overnight rates that make EV miles even less expensive.

Use blended math

Maintenance and repairs: fewer parts, different risks

EVs remove entire systems, oil changes, exhaust, multi‑gear transmissions, that drive much of the maintenance budget in gas vehicles. But they introduce a large battery pack and new electronics. Over a 5‑year span, most mainstream EVs are cheaper to maintain than comparable gas cars, but not every model is a slam‑dunk on total cost of ownership.

Typical maintenance profile: electric vs gas

These are broad patterns for mainstream vehicles over the first 5–8 years of ownership, assuming normal use and no major accidents or component failures.

| Item | Gas vehicle | Battery‑electric vehicle |

|---|---|---|

| Oil & filters | Regular oil changes, engine air filter replacements | Not required |

| Transmission service | Fluid changes and, in some cases, repairs | Usually a simple single‑speed unit with minimal service |

| Brakes | More wear; friction brakes do most of the work | Less wear thanks to regenerative braking |

| Cooling system | Engine coolant flushes, hoses, water pump | Battery and motor cooling; usually lower service frequency early in life |

| Ignition & exhaust | Spark plugs, ignition coils, catalytic converters, mufflers | Not applicable |

| Software & electronics | Some updates at the dealer | Frequent over‑the‑air updates; some paid features tied to software |

Routine maintenance differences between EVs and gasoline vehicles.

The big‑ticket risk: batteries

Emissions: are EVs really cleaner than gas cars?

EV critics often point out that building batteries is energy‑intensive and that electricity still comes partly from fossil fuels. Both are true. What matters is the lifetime picture: manufacturing plus driving. Recent peer‑reviewed research finds that EVs typically start out with a higher emissions footprint during production but “catch up” to comparable gas cars within the first few years of driving, then pull ahead for the rest of their lives.

- Battery manufacturing makes an EV roughly 20–30% more carbon‑intensive to build than a comparable gas car today.

- By around year 3 of typical U.S. driving, the EV’s lower operating emissions usually erase that advantage.

- Over a full lifecycle, a comparable gas vehicle often causes roughly twice the climate impact of a battery‑electric vehicle, especially as the grid gets cleaner.

Grid is trending cleaner

Range, charging, and living with each type day to day

The biggest lifestyle gap between electric and gas vehicles isn’t cost, it’s convenience and flexibility. Gas cars win on refueling speed and rural coverage; EVs win on the convenience of fueling at home and in dense metro areas, assuming you’ve got access to a reliable charger.

Gasoline vehicles

- Range: 350–450 miles per tank is common.

- Refueling: 5 minutes at ubiquitous gas stations.

- Best for: Drivers without home charging, frequent rural travel, towing, and spontaneous long trips.

Battery‑electric vehicles

- Range: Many new EVs offer 230–320 miles EPA‑rated range; used models may have less.

- Charging: Level 2 home charging adds 25–40 miles of range per hour; DC fast charging can add ~150 miles in 20–35 minutes on capable models.

- Best for: Predictable commutes, households with home or workplace charging, frequent city or suburban driving.

Apartment and street parking reality check

Resale value, depreciation, and battery health

Resale is where the story gets nuanced. For years, gas vehicles held value better than many EVs, partly because shoppers were uncertain about battery longevity and future incentives. At the same time, some EVs, especially Teslas, held up well in certain model years, then were hit by sudden price cuts on new models.

What drives resale value for electric and gas vehicles

Think beyond the badge on the hood.

Battery health & warranty

On EVs, remaining battery capacity and years/miles left on the battery warranty are huge drivers of resale value. A documented health report is a major plus.

Fuel economy & gas prices

On gas vehicles, future fuel prices and EPA mpg ratings heavily influence resale. When gas spikes, efficient models and hybrids gain an edge.

Policy & incentives

Shifts in EV incentives and emissions rules can suddenly make certain powertrains more or less attractive in the used market.

Why battery reports matter when buying used

Which vehicle is right for you? Scenarios and examples

Match electric and gas vehicles to real‑world scenarios

1. Mostly city driving, off‑street parking

If you drive under ~60 miles most days and have a driveway or garage, a full EV is often the best fit. You’ll benefit from low per‑mile energy costs, minimal maintenance, and the convenience of charging at home. Gas vehicles only make sense here if you road‑trip constantly or can’t install a charger.

2. Long rural commutes, no home charging

If you live in a rural area with sparse charging and rely on street parking or shared lots, a fuel‑efficient gas car or hybrid often beats a full EV. A plug‑in hybrid can be a sweet spot if you have at least occasional access to reliable Level 2 charging.

3. Two‑car household

Many households do best with a mix of <strong>electric and gas vehicles</strong>. Make the high‑mileage, predictable‑route car (commuter, school run) electric, and keep a gas or hybrid vehicle for towing, long trips, or irregular use.

4. Heavy towing and frequent road trips

Today’s EV pickups can tow impressively, but range drops sharply with heavy loads and chargers near campgrounds or job sites can be hit‑or‑miss. If you tow often or drive long distances where fast chargers are scarce, a gas or diesel truck, or possibly a plug‑in hybrid, remains the safer choice.

5. Budget‑limited buyer, keeping car 10+ years

If you can find a well‑priced used EV with a strong battery report, it may deliver the lowest total cost of ownership thanks to fuel and maintenance savings. If not, a simple, efficient gas car or hybrid with a solid reliability record is a safer bet than stretching to an expensive new EV just for the technology.

Practical decision roadmap

Leaning electric

Confirm you’ll have consistent access to home or workplace charging.

Check your true daily miles, not just worst‑case trips.

Compare total 5‑year cost (payment + electricity + maintenance) to a comparable gas or hybrid option.

For used EVs, insist on a battery health report and check remaining warranty coverage.

Leaning gasoline or hybrid

Estimate your annual fuel cost at a few different gas price scenarios.

Compare a hybrid to your preferred non‑hybrid gas model; the upfront premium may pay back quickly.

Consider whether a plug‑in hybrid could cover most local driving on electricity while preserving gas flexibility.

If you later add home charging, you can always make your next vehicle fully electric.

FAQ: electric and gas vehicles

Frequently asked questions about electric and gas vehicles

Bottom line: how to decide with confidence

Electric and gas vehicles each bring real strengths and real trade‑offs. Gas cars still own long‑distance convenience and rural flexibility; EVs excel at low running costs, quiet performance, and cutting emissions, especially when you can charge at home. Hybrids and plug‑in hybrids often make sense in the messy middle.

The key is to stop thinking about what’s “winning” the market and focus on what fits your life. Map your actual driving, be honest about your charging options, and compare specific models on total cost of ownership, not just sticker price. If you’re EV‑curious but hesitant, starting with a used electric vehicle can be a smart way to capture most of the benefits with less financial risk, provided you understand the battery’s health and the vehicle’s history.