You’ve heard the horror stories: the electric car that becomes worthless when the battery dies, the five‑figure replacement bill lurking just over the horizon. The reality of the life of a battery in car batteries is far less dramatic, and far more interesting. Modern EV packs are proving to be marathoners, not sprinters, quietly outlasting the cars wrapped around them.

Big picture

How long do electric car batteries really last?

What recent data says about EV battery life

For a typical modern EV sold in North America, you should expect the main traction battery to last at least as long as a gasoline car’s engine and transmission, often longer. In everyday terms, that means 150,000 to 250,000 miles, or roughly 12–20 years of normal use before capacity loss becomes limiting for most drivers.

Most carmakers back this up with an 8‑year battery warranty, usually around 100,000 miles in the U.S., and many go to 120,000 or 150,000 miles. Real‑world data from fleet vehicles, taxis, and early‑adopter EVs shows that packs frequently beat those expectations, retaining the bulk of their usable range well into six‑figure mileage.

Rule of thumb

What does “battery life” actually mean in an EV?

When people talk about the life of a battery in a car, they’re usually mashing together three different ideas:

- Calendar life – How many years the pack lasts before it’s considered at end‑of‑life.

- Cycle life – How many charge–discharge cycles it can handle before capacity falls to a given threshold.

- Useful life for you – The point where reduced range or performance no longer fits your daily driving, even if the battery isn’t technically “dead.”

Unlike a phone battery that suddenly feels useless after a few years, an EV pack doesn’t fall off a cliff. It simply loses a bit of capacity each year. Industry and research convention generally call an EV battery at “end‑of‑life” for automotive use around 70–80% of its original capacity. The pack still works; you just get less range per charge.

How EV batteries age and lose capacity

Under the skin, your EV’s battery pack is a carefully managed hotel for lithium ions. Every time you drive, ions shuttle between the positive and negative electrodes. Over thousands of these trips, a few things inevitably happen: surfaces roughen, side reactions create gunk, a bit of lithium gets tied up and can’t move freely. The chemistry ages.

Two main types of EV battery aging

Same idea as human aging: part time, part lifestyle

Calendar aging

Happens just because time passes.

- Even if you don’t drive much

- Faster when parked hot and full

- Slower in moderate temperatures

Cycle aging

Comes from using energy in and out.

- More full cycles = more wear

- Deep discharges are harder on cells

- Fast charging adds extra stress

In practice, you never see this chemistry directly. You see it as a slow, almost boring story: the car that once delivered 280 miles on a summer road trip now does 255; the DC fast charge that used to jump you from 10% to 60% in 18 minutes now takes 21.

The silent killer: heat

7 factors that shorten the life of car batteries

The main culprits behind faster EV battery wear

1. Living at high state‑of‑charge

Parking at 90–100% for days at a time keeps cell voltage high and speeds chemical breakdown. Topping up to 100% right before you leave is fine; keeping it there all weekend is not.

2. Frequently running near empty

Regularly dipping below ~10% state‑of‑charge forces cells into a low‑voltage zone that they don’t like. Occasional deep runs are OK; making it your habit will cost you capacity over time.

3. Heavy fast‑charging use

Repeated DC fast charging, especially at high power on a hot day, raises pack temperatures and accelerates aging. Modern packs manage this better than early EVs, but it still adds wear vs slower AC charging.

4. High ambient heat

Parking in direct sun on a hot asphalt lot, day after day, is hard on any lithium‑ion chemistry. Garages, shade, and lighter‑colored cars help more than most people realize.

5. Aggressive driving and towing

Frequent full‑throttle launches, high‑speed runs, or towing heavy loads draw large currents from the pack. Automakers design for this, but if every drive is a track day, you’ll pay in battery life.

6. Poor thermal management

Not all EVs are created equal. Cars with robust liquid‑cooled battery systems generally handle heat and fast charging better than those with minimal or passive cooling.

7. Cheap or botched repairs

Improper battery repairs, coolant leaks, or crash damage that isn’t handled by a qualified shop can create hot spots and accelerate degradation, or, in the worst case, safety issues.

Don’t panic about the occasional road trip

How to make your EV battery last longer

If the previous section sounded like a list of sins, this one is your redemption arc. You don’t have to baby an EV, but a few easy habits can stretch the life of a battery car battery considerably.

- Aim to keep your day‑to‑day charge window roughly between 20% and 80% when practical.

- Use DC fast charging as a tool for trips, not your daily bread and butter.

- Whenever possible, park in a garage or shaded area, especially in summer.

- If you’re leaving the car parked for weeks, set it around 40–60% and let the car sleep.

- Use scheduled charging so it finishes shortly before you depart, rather than sitting full for hours.

- Keep your software up to date; many automakers tweak battery management over time.

- If the car lets you limit max charge (say to 80% or 90%), take advantage of it for routine use.

Good news for lazy owners

Battery warranties: what they really cover

In the U.S., EV battery warranties cluster in a surprisingly tight band. Automakers typically promise something like 8 years / 100,000 miles against excessive capacity loss, often defined as dropping below 70% of original capacity within the warranty period. Some go further, with higher mileage caps or longer terms on certain models.

Typical EV battery warranty patterns

Exact terms vary by brand and model, but these patterns are common for modern EVs.

| Brand (example) | Typical term | Mileage cap | Capacity guarantee |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mainstream brands | 8 years | 100,000 miles | ~70% |

| Some premium models | 8–10 years | 120,000–150,000 miles | ~70% |

| Short‑range city EVs | 8 years | 100,000 miles | May not specify capacity |

| Early compliance EVs (used) | 5–8 years | 60,000–100,000 miles | Often weaker or expired by now |

Always read the fine print, some warranties cover only total failures, others explicitly cover capacity loss.

The key nuance is capacity vs. failure. A pack that still holds, say, 72% of its original energy and drives fine probably isn’t covered, even if its reduced range annoys you. Warranties are there to catch outliers, defective packs, runaway degradation, not the normal, slow fade everyone experiences.

Watch the warranty on older used EVs

Used EVs and battery life: what shoppers should know

On the used market, the life of a battery isn’t an abstract chemistry lecture, it’s dollars and daily range. Two otherwise identical cars can feel very different if one pack has lived a pampered suburban life and the other survived three ride‑share tours of duty and a Phoenix summer.

Battery questions to ask when buying a used EV

Because "seems fine on a test drive" isn’t enough anymore

What’s the real battery health?

Ask for objective data, not just a guess.

- Has the pack been capacity‑tested?

- Any degradation report or battery certificate?

- How does that compare to similar cars?

What’s left on the warranty?

Confirm in writing.

- Original in‑service date

- Years and miles remaining

- Any exclusions for commercial use or fast‑charging?

How was it charged and used?

History matters.

- Home charging vs. fast‑charging heavy

- Hot or cold climate use

- Fleet, rideshare, or private owner?

Where Recharged fits in

Why generic range isn’t enough

A seller can tell you, truthfully, that a car still shows 240 miles of range on a full charge. But without context, original rated range, climate, usage, pack chemistry, that number isn’t very helpful. A healthy long‑range crossover and a tired short‑range hatchback might both show 200‑ish miles on a good day.

What a real battery report adds

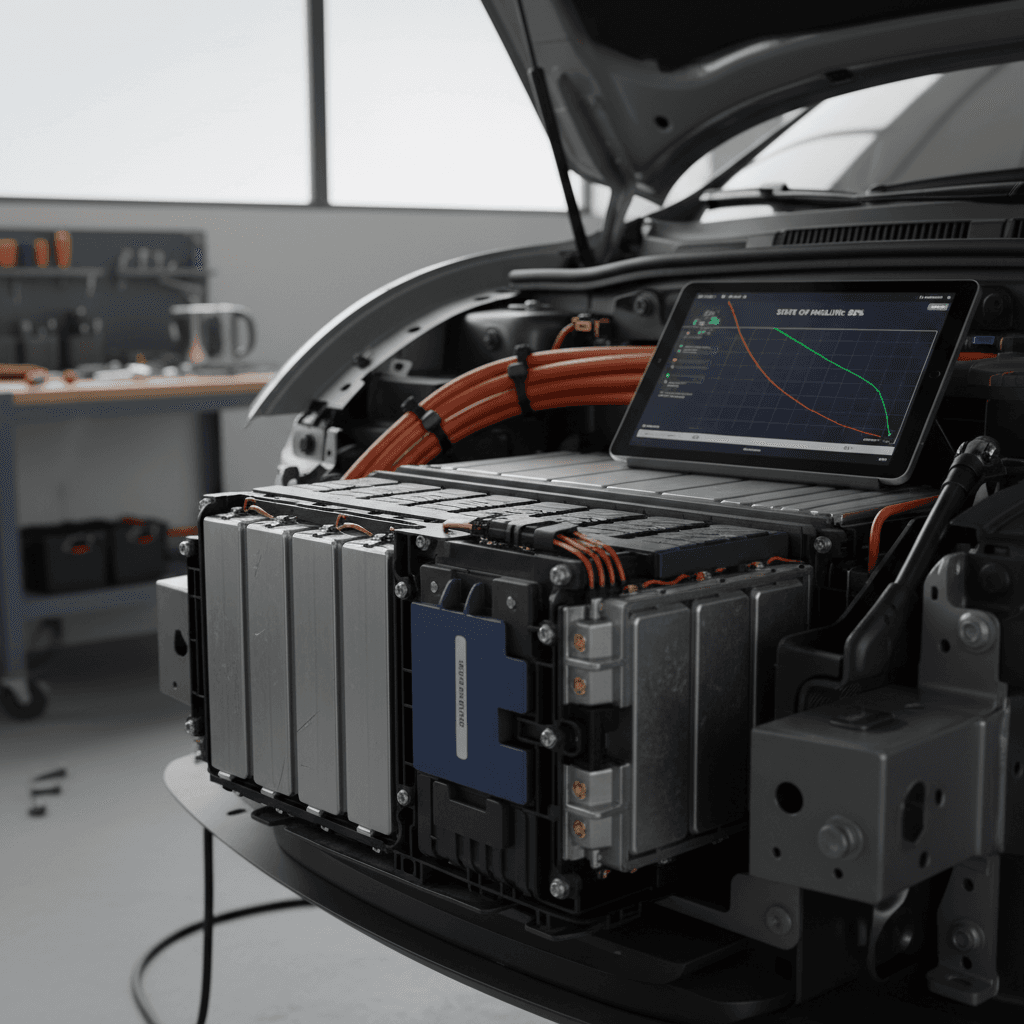

Recharged’s battery diagnostics dig into usable capacity, pack balance, and charge behavior over time. Instead of a shrug and a test drive, you see how that car compares to similar models and what you can realistically expect for years to come.

Second life and recycling: what happens after the car

When an EV battery pack can no longer deliver enough range for comfortable daily driving, it doesn’t suddenly become toxic trash. At 70–80% capacity, it’s still perfectly capable of doing steady, lower‑power work, and that’s where second‑life applications come in.

- Stationary storage – Retired EV packs are increasingly repurposed into battery farms that soak up solar and wind energy, then feed it back to homes and grids when needed.

- Commercial backup – Warehouses, data centers, or EV charging depots can use second‑life packs as buffers to shave peak demand charges.

- Microgrids and off‑grid cabins – Compact, modular battery racks built from ex‑EV cells can store power for remote communities.

Eventually, even these second careers end. The next act is recycling. Modern processes can already recover a large share of valuable materials, lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper, aluminum, for use in new cells. As volumes scale, the economic incentive to harvest those metals only improves.

The loop is closing

FAQ: Life of a battery in electric cars

Frequently asked questions about EV car battery life

The story of the life of a battery in modern car batteries is not one of fragile chemistry and looming catastrophe. It’s a story of quiet durability: packs that grind through hundreds of thousands of miles, then settle into second careers storing clean energy, and finally surrender their metals to be reborn in the next generation of cells. If you’re shopping for an EV, especially a used one, the question isn’t “Will the battery explode my budget?” It’s “Do I have the right information to understand how much life is left?” That’s the gap Recharged is built to close.