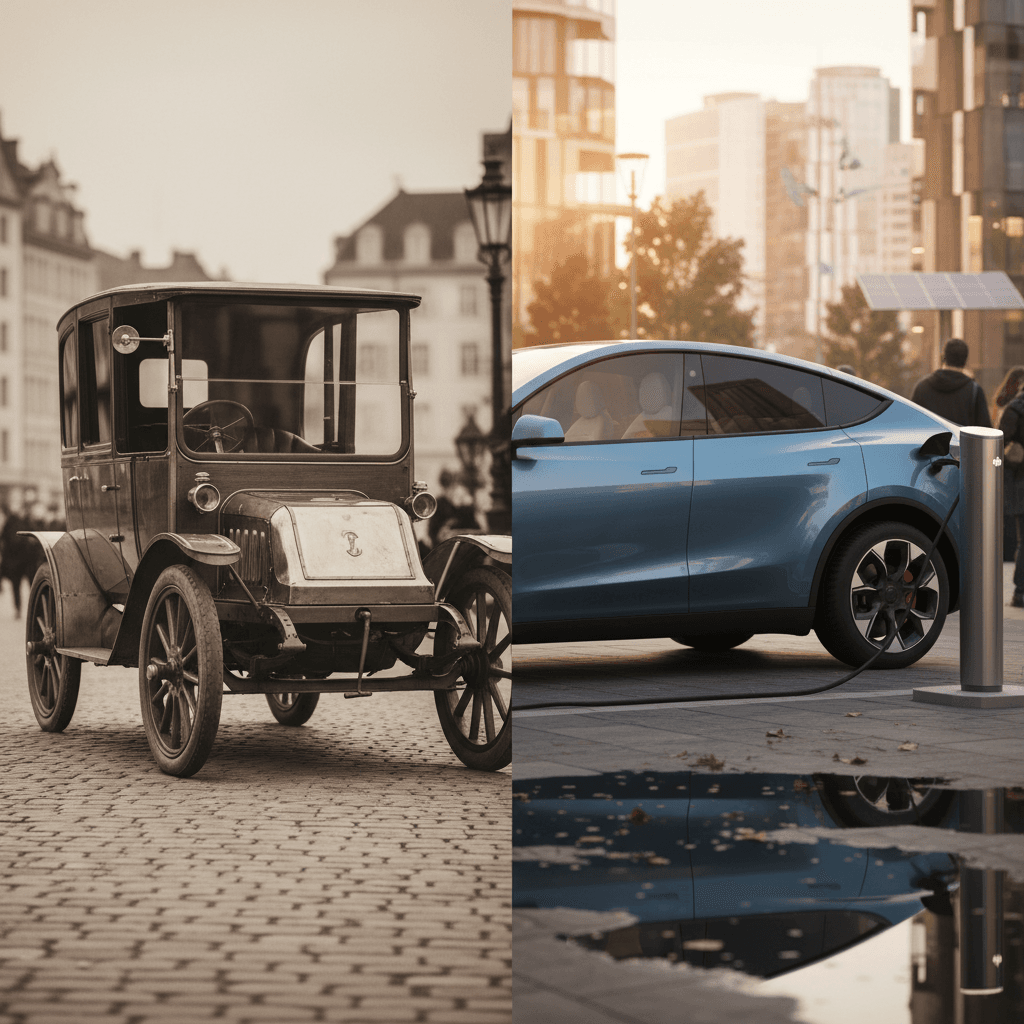

When people ask about the first hybrid car, they’re usually expecting a simple name and a year. Instead, you get an argument. Was it an obscure coach built in 1900, or the Toyota Prius that stormed into showrooms a century later? The truth is more interesting, and it explains why hybrids are suddenly selling like hotcakes while the fully electric future takes a breath and glances nervously at the charging map.

Short answer

What actually counts as the first hybrid car?

Ask three engineers what the “first hybrid car” is and you’ll get four opinions. To keep things honest, you need two basic criteria:

- It must use both an internal‑combustion engine and an electric motor in the same vehicle.

- The electric side must be more than a gimmick, its job is to meaningfully assist propulsion or efficiency, not just power the headlights.

By that standard, most historians point to Ferdinand Porsche’s Lohner‑Porsche Semper Vivus in 1900 as the first true hybrid car: a gas engine driving a generator, feeding electric motors in the wheel hubs. A rolling science project, yes, but also a genuinely new way of thinking about how to move a car.

Don’t confuse “first hybrid” with “first popular hybrid”

Lohner‑Porsche Semper Vivus: the original hybrid (1900)

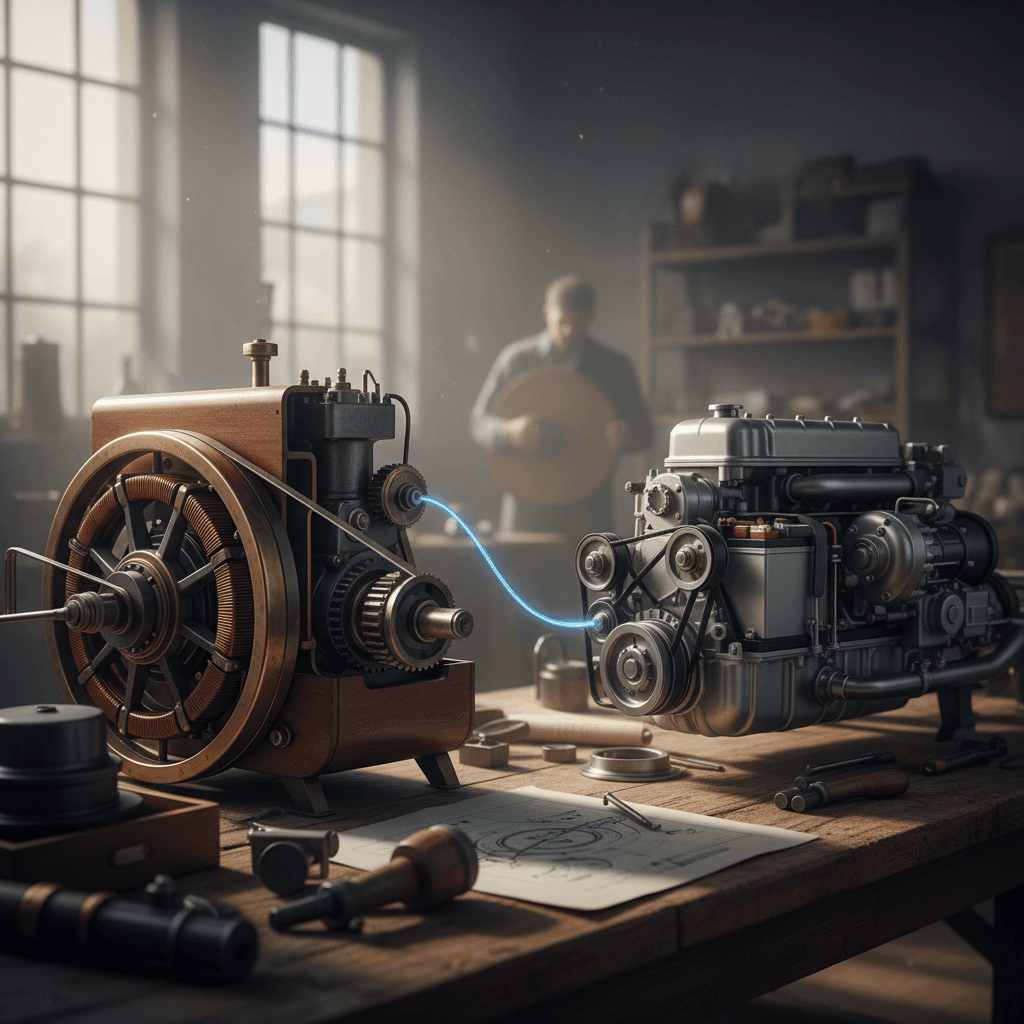

At the turn of the 20th century, cars themselves were a weird new technology, roughly as exotic as consumer robots are today. Into that chaos stepped a young engineer named Ferdinand Porsche working for coachbuilder Lohner in Vienna. His big idea: use electricity to tame the crude, noisy gasoline engine.

- A small gasoline engine powered a generator.

- That generator sent electricity to motors in the wheel hubs.

- There was no mechanical driveshaft at all, just wires and gears.

- Some versions had batteries that could store extra energy, making them an early series hybrid.

On paper, it was brilliant. In practice, it was heavy, expensive, and born into a world where gas was cheap and nobody cared about emissions or efficiency. The Semper Vivus and its production cousin, the Lohner‑Porsche Mixte, sold in tiny numbers, technically impressive, commercially irrelevant.

Why this oddball matters now

From laboratory trick to showroom: Prius and the first mass‑produced hybrid

Fast‑forward to the 1990s. Oil shocks, urban smog and climate science had finally convinced automakers to treat efficiency as more than a marketing slogan. Batteries and power electronics had matured. What Porsche couldn’t sell in 1900, Toyota was ready to bet the house on in 1997.

From one‑off experiment to global product

Two cars that define "first hybrid" depending on who you ask

Lohner‑Porsche Semper Vivus (1900)

- Type: Experimental series hybrid

- Production: Essentially prototypes and very low volume

- Goal: Explore electric propulsion using a gas generator

- Legacy: Engineering legend, no mass‑market impact

Toyota Prius (1997, 2000 globally)

- Type: Mass‑produced parallel hybrid sedan

- Production: Hundreds of thousands in first generation, millions since

- Goal: Drastically cut fuel use in real‑world traffic

- Legacy: The car that made "hybrid" a household word

The first‑generation Toyota Prius launched in Japan in 1997 and went global around 2000. It wasn’t the first hybrid ever built, but it was the first that an ordinary buyer could walk into a dealership and finance like any other compact sedan, and then quietly double their fuel economy.

Toyota’s masterstroke was not the technology so much as the packaging. The Prius looked odd enough to signal virtue, but not so odd that you couldn’t park it at the office. It drove like a normal automatic. No plugs, no range anxiety, just fewer trips to the gas station.

So which was “first”?

How hybrids work, in plain English

Ignore the wiring diagrams for a moment. Every mainstream hybrid, from an early Prius to a modern hybrid pickup, is doing one simple thing: trading hardware for software. You let computers juggle power between an engine and an electric motor so the engine can stay in its happy zone and the motor handles the ugly bits.

Core ingredients of a modern hybrid

1. Gasoline engine

Smaller than in a comparable non‑hybrid, tuned to run efficiently rather than heroically. Think steady jog, not repeated sprints.

2. Electric motor (or motors)

Adds torque at low speed, fills in during gear changes, and can move the car briefly on electricity alone in many designs.

3. Battery pack

Much smaller than a full EV battery. Stores energy recovered from braking and from moments when the engine has more power than you need.

4. Power electronics & brain

Inverters and control software orchestrate who does what. This is where modern hybrids quietly out‑think physics.

5. Regenerative braking

Instead of turning motion into heat at the brake discs, the motor works as a generator and feeds energy back into the battery.

Two main flavors: hybrid vs plug‑in hybrid

Hybrid timeline: from 1900 to today’s sales boom

Hybrids by the numbers

Key milestones in hybrid history

A century of tinkering between gas and electric power.

| Year | Event | Why it Matters |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | Lohner‑Porsche Semper Vivus prototype | First functional hybrid drivetrain combining gas engine, generator and electric motors. |

| 1901–1905 | Lohner‑Porsche Mixte limited production | Early series‑hybrid coachwork; technically daring, commercially niche. |

| 1960s–1970s | Concept hybrids from major automakers | GM, others experiment with range‑extender and plug‑in concepts as oil shocks hit. |

| 1997 | Toyota Prius launches in Japan | First mass‑produced hybrid car sold to everyday drivers. |

| 1999 | Honda Insight arrives in the US | First hybrid on sale in North America; ultra‑efficient two‑seater with assist motor. |

| 2004–2010 | Second‑gen Prius & rivals | Hybrids move from eco‑novelty to mainstream commuter choice. |

| 2010s | Hybrid SUVs and pickups | Tech spreads to larger vehicles; efficiency gains where they matter most for fuel use. |

| 2020s | Hybrid boom alongside EVs | Hybrids surge as a "just‑right" option for buyers not ready to go fully electric. |

From boutique experiments to mainstream commuter cars, hybrids have been a slow‑burn revolution.

Why hybrids are booming again

Hybrids vs EVs: what the first hybrid started

What hybrids do well

- Range without anxiety: Hundreds of miles on a tank, plus better MPG in traffic.

- No charging homework: Great if you live in an apartment or can’t easily install home charging.

- Lower entry price: Hybrids typically cost less than comparable EVs and often less than plug‑in hybrids.

- Bridging technology: Uses less fuel today while the charging grid catches up.

Where EVs have the edge

- Zero tailpipe emissions: Nothing coming out the back, which matters in dense cities and for climate goals.

- Simpler drivetrain: No engine, no oil changes, fewer moving parts to wear out.

- Instant torque: Performance that would’ve seemed like science fiction in 1900.

- Home fueling: If you can install a Level 2 charger, “refueling” becomes an overnight background task.

Seen from 30,000 feet, the first hybrid car was less a quirky dead‑end and more a preview. Ferdinand Porsche’s Semper Vivus said, in effect, “Why pick one energy source?” Today’s market gives you that same choice at the dealership: burn fuel more intelligently in a hybrid, or skip it entirely in an EV.

Where hybrids fall short long‑term

Thinking of a used hybrid? What to watch for

If the story of the first hybrid car has you eyeing a used Prius, Accord Hybrid or RAV4 Hybrid, the good news is that hybrids have matured into some of the most durable commuter machines on the road. But you are layering battery and software complexity on top of an engine, so going in with eyes open matters.

Used‑hybrid checklist for real‑world buyers

1. Battery health, not just age

High‑voltage packs can last well over 150,000 miles, but they don’t all age the same. Look for a <strong>battery health report</strong> rather than assuming based on model year alone.

2. Service history

Hybrids still need regular oil changes, coolant service and sometimes transmission fluid. A thick folder of receipts beats any salesman’s handshake.

3. Hybrid‑system warnings

On a test drive, the dash should be free of hybrid‑system warning lights. If you see the equivalent of a Christmas tree, walk away or negotiate as if a battery is in your near future.

4. Real‑world fuel economy

Compare the car’s current MPG to period EPA ratings. A big gap can hint at battery degradation, dragging brakes or tired tires.

5. Charging needs vs driving pattern

If most of your drives are short and predictable, a used <strong>plug‑in hybrid</strong> might slash fuel use even further. If you road‑trip constantly, a regular hybrid may be simpler and cheaper.

6. Total ownership math

Factor in potential battery replacement costs, fuel savings and maintenance when you compare a used hybrid to a used EV or conventional car.

Where Recharged fits in

FAQ: the first hybrid car and today’s market

Frequently asked questions

Key takeaways from 125 years of hybrids

- The first hybrid car most historians recognize is the Lohner‑Porsche Semper Vivus from 1900, brilliant, rare, and way ahead of its time.

- The first mass‑produced hybrid that regular people actually bought in volume was the Toyota Prius, starting in 1997 in Japan and around 2000 globally.

- Hybrids took off once electronics, batteries and regulations aligned; today they’re a comfortable middle ground between gas and full EV.

- If you’re shopping used, battery health and service history matter far more than model‑year bragging rights.

- When you’re ready to explore a used EV as your next step, Recharged makes the jump from gas or hybrid transparent, with verified battery diagnostics, expert guidance and nationwide delivery.

The first hybrid car wasn’t built to win a marketing war or chase tax credits. It was built by an engineer who couldn’t stand wasted energy. A century later, you’re spoiled for choice: efficient hybrids, confident plug‑in hybrids, and increasingly capable EVs. The right move now is to pick the technology that fits your life today, without closing the door on tomorrow. If that next step is a used EV, Recharged is here to make sure the numbers, and the battery, actually add up.